WORDS: CASS NAVARRO

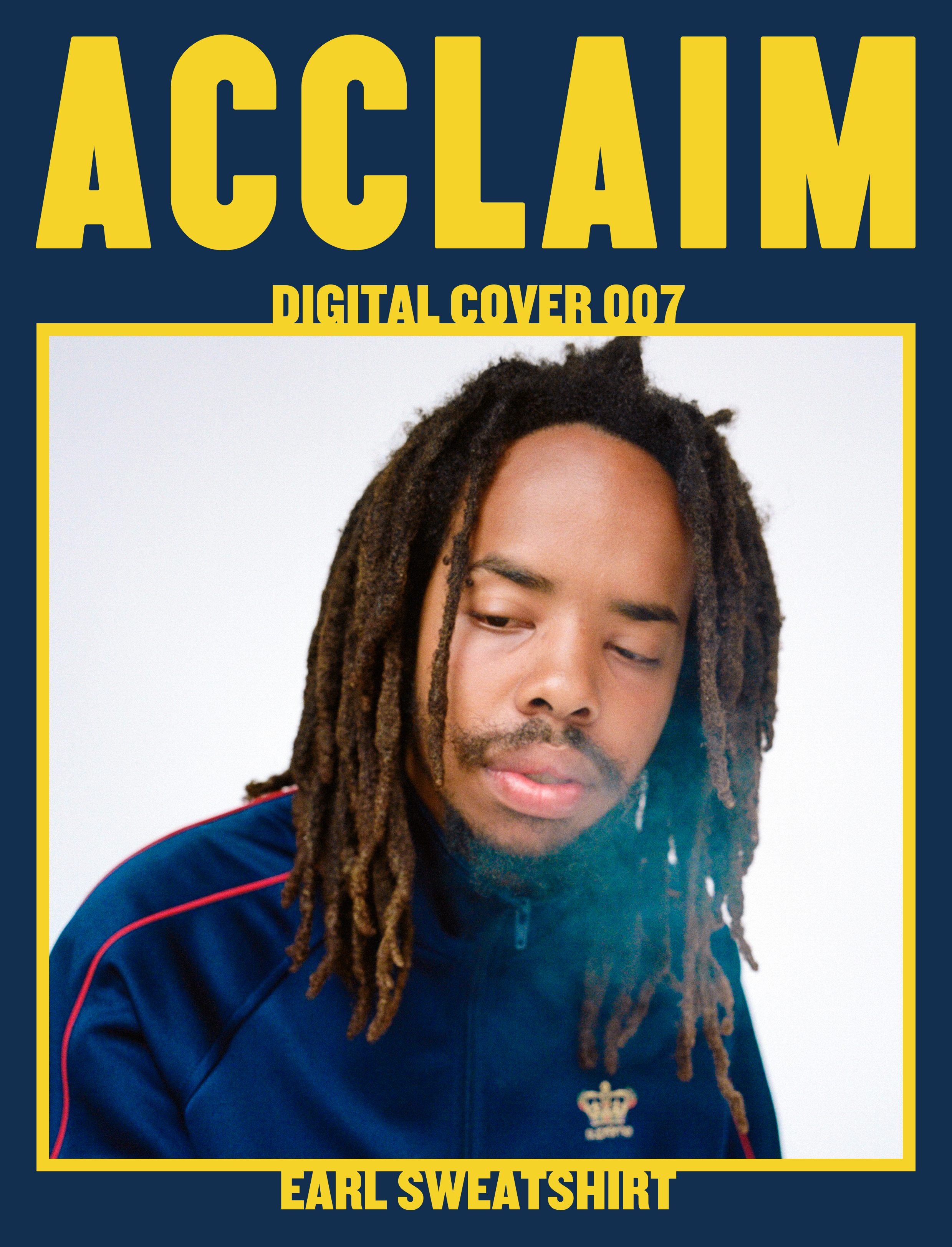

Thebe Kgositsile has lived more than a third of his life in public view, as Earl Sweatshirt, the prodigious rap talent who came up at 16 during the Odd Future boom. Over the seven-odd years since his debut album Doris, Thebe’s developed a to-be-expected degree of psychic distance from Earl, as much as any twenty-something would from their teenage self. With his latest album, Feet of Clay, it’s clear that Earl Sweatshirt is a very different project than it once was, 'cause the man himself is older and certainly wiser.

Thebe was born in Chicago and raised in LA, where still lives today. His mother, UCLA law professor Cheryl Harris, sent him Samoa for a brief period as a teenager to straighten out, roiling his young fans. His father, Keorapetse Kgositsile, was widely respected South African poet who passed away in 2018. Lately, both of Thebe's parents have made frequent appearances in his music, through lyrics gesturing at family dynamics and, more explicitly, in 2018's ‘Play Possum’ which samples their speech and formally credits them with features.

Feet of Clay, released through Earl’s own imprint Tan Cressida, is remarkably short: only two of its seven songs clock in over two minutes. Earl’s delivery is deliberately imprecise and at-ease, skimming over lo-fi, loosely mixed beats. Guest verses come from protégé MAVI, frequent collaborator Mach-Hommy, and Dallas artist Liv.e. Once brash and provocative, Earl’s lyrics are more abstract, peppered with mythological references, often reflecting his personal appetite for knowledge.

Speaking with Acclaim over the phone from Sydney, where he'd stopped off with Laneway Festival, Thebe is an easy conversationalist, cautious not to have his work misinterpreted.

You've made a few trips down here already. You’re a young guy, but you’ve been touring for almost a decade.

Absolutely, that's the thing. I may have put in 10 but I'm still a baby. It's all about staying young, but not in a vampiric way. It means always being open to learn, thinking critically and being open.

What have you been reading lately?

I'm reading about the CIA's involvement in Angola and Mozambique. I'm reading Blues People by Leroi Jones, and I'm listening to Billy Woods. I'm listening to Elucid in my car. Music is still a source of a lot of information for me. If you’re paying attention, it helps you make sense of life. People used to walk around in the Renaissance era and even [if] you wasn't really like an aristocratic type person, you'd still have quotes from poetry on deck. [Art] helps you make sense of life, because it draws from experience, and I think nothing has changed. Music helps us make sense of life.

You came into the spotlight at a young age, but you've never appeared to make commercial compromises to your music. How did you manage that?

By being very stubborn. I say No a lot. People try and pimp music and end up hoeing themselves.

After Some Rap Songs you said that you wanted to do "riskier shit." Would you say that’s true for Feet of Clay?

I'd say Feet of Clay is a heat-check. And what I mean by that is like, yeah.

Some of the critical assessment of Clay as a ‘risky’ project comes from the track ‘EAST’, because the beat feels left-of-centre for rap today. Can you tell me more about that track?

Bro, everybody calls it left-of-centre because it's not like, stock. But the thing is, there's an area of the world where that loop is stock. That's the whole thing about presenting things to [audiences] with a fucking Euro-centric world view—it’s going to 'other' everything. The rest of the world is way bigger than Europe, that's my whole thing. Where I'm from the name ‘David’ is weird, you know what I'm saying?

Absolutely. After Clay, where do you see your music going next?

Things have always got to evolve, that's just the nature of life. [I’m] allowing it to develop naturally. It's always about being open, keeping an open ear, learning and remembering. Yo, what you been listening to

Here in Australia, there's this new wave of Pacific Islanders doing drill.

Bruh, he said the Poly-drill! Nah, I'm hip bro—I seen it on the internet. That shit is kinda stressful bruh. I feel like it speaks to the violence in the world, for people to relate to drill music.

.jpg?alt=media&token=2d65f01c-8b92-45a9-bca2-0239923c22c0)

I’ve seen a lot written about an interview you did with your father years ago. It’s not easy to find these days. What was that experience like for, not long after releasing a song like Chum.

That was a really confusing time for me. I had just gotten home from Samoa, and then having to engage my father—not just as my father, but now as two people in the public eye—it was very strange. I had a big mental block against that until damn near fairly recently. Even in his death I had a hard time processing both of us existing in the public eye, just processing that that nigga is my father at the end of the day. Regardless of who people are, that's still the person that is my father.

Last year you said you wanted to become more self-sufficient by growing your own food and weed. How’s that going?

Man! I haven't even been home like that yet. Once I'm more stable, then I can put down some seeds.

How did you feel seeing Tyler win the Grammy?

Oh man, salute. I know that nigga really wanted that. That's a dude that gets what he wants, that's crazy.

What are your most important memories from the last ten years in music?

Memories of having my heart broken and being physically broken down, but still recovering from those things.

With the EARL tape turning 10 in March, what would present-day Earl say to 2010 Earl?

Oh man, are you in for some fucking surprises my nigga. That's what I would say to him. You're in for some crazy times. 'Cause there ain't nothing I could say that would save me from the conflict I needed to go through then to become who I am today.